What if we’ve misunderstood one of the most quoted verses in the Bible?

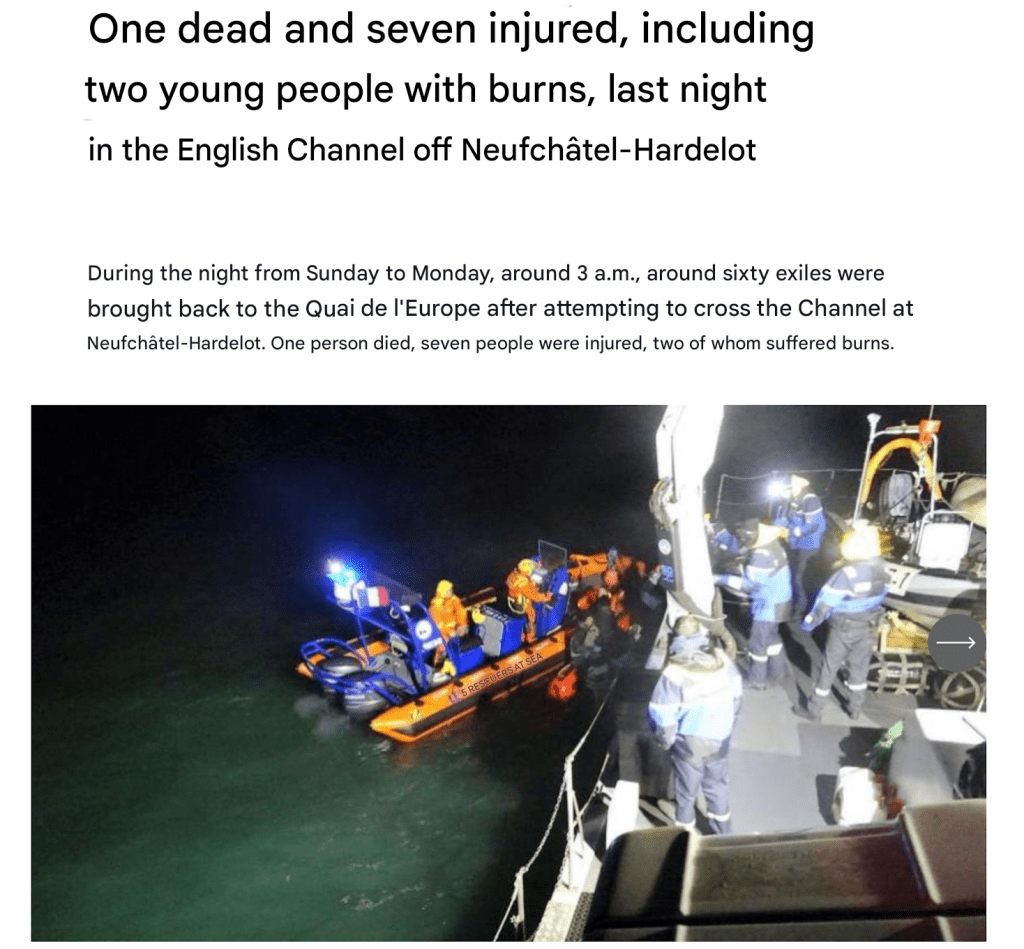

What I’m speaking of is Psalm 46:10. I learned this verse as a young person, and we always used the King James Version (KJV), so this is how I memorized it:

“Be still, and know that I am God: I will be exalted among the heathen, I will be exalted in the earth.”

An Incomplete Understanding

It’s not a bad translation, exactly. However, in my youth, the part where it says, “Be still and know” was always emphasized. It specifically meant that the Christian should make time and space to quiet their heart. They should sit in calm and silence with God to experience his presence. (Again, God was always male.)

Not bad advice, right?

On the one hand, no, it’s not bad advice at all. In fact, I’ve often found myself reflecting on this passage in that sense. I feel that I am closest to God when I am by myself, specifically in nature. I think that’s true for many people. For me, sitting on a log in the middle of the forest is an ideal opportunity to spend time communing with the Most High. It’s a beautiful thing.

But the problem is, that’s not exactly what this passage is talking about.

When reading Scripture, context is always important. If there’s one thing I’ve kept from my days in Bible college, that’s it. So if we read this verse in context we can get a better picture of what’s meant here:

“He maketh wars to cease unto the end of the earth; he breaketh the bow, and cutteth the spear in sunder; he burneth the chariot in the fire. Be still, and know that I am God: I will be exalted among the heathen, I will be exalted in the earth” (Psalm 46:9, 10, KJV).

While it’s pretty clear in the KJV version, I prefer other translations, like this one:

“God brings wars to an end all over the world. He breaks the arrows, shatters the spears, and burns the shields. Our God says, ‘Calm down, and learn that I am God! All nations on earth will honor me’” (Contemporary English Version (CEV)).

A More Complete Picture

While this is perhaps more of a paraphrase than a direct translation, I think it does a better job of capturing the intent of the passage. The text of Psalm 46:10 is directly related to the ending of war and strife. In this passage we have a God who ends wars and violence, destroying weapons and ending conflict.

I love the way the CEV translates it as, “Calm down, and learn that I am God!” I think this is the thing that we miss when we simply take it at face value. Other translations I’ve seen say “Stop fighting” or “Cease striving.” These let us know that God wants all conflict to cease and for everyone to turn to God and “learn that I am God.”

Since I’m a nerd and I don’t know Hebrew, I looked up an interlineal translation of this verse. I really like what it has to say about the “know that I am God” section. The Hebrew word meaning “know” here is transliterated as yada`, and the main meaning of the word is “to know (properly, to ascertain by seeing)” (source).

That idea of “to ascertain by seeing” is extremely important. So basically, what we’re getting from this passage is, “Stop your striving and pay attention so that you can see that I am God.”

There is a lot that we can take away from this, but I’ll leave it at two primary things.

First, the sense of the passage that I was brought up to understand isn’t necessarily wrong, but it is incomplete.

Second, God calls on us to end our conflicts with each other and to pay attention and learn that God is God.

So What Now?

So what can we do about this? For one, we can recognize that our wars and conflicts with each other are virtually meaningless and not very important. God has called us to put down our weapons.

This part seems easy for me, because I embraced pacifism when I became a Mennonite. But as I write this I wonder how many useless conflicts I’ve partaken in during my life, even nonviolent ones. This is a call for me to lay down my (metaphorical) weapons and look upward.

Second, we can “know” that God is God, or as the CEV translates it, “learn that I am God.” We can observe the ways that God is working in our world and acknowledge that God is over all things.

We can open our hearts to the peace that comes with knowing that we are not alone and our lives are important to the One who created us.

We are loved and beloved, but we so often stray from that love into meaningless conflicts and wars, whether personal or international.

Perhaps we can focus on learning that God is God when we quiet our hearts and our minds.

Maybe God can be found in places where we are less likely to look. Maybe God’s presence is found in a still, small voice, like the experience Elijah had on the mountain. All we need to do is stop fighting and listen.