Shane Claiborne, what can I say. In the story of my spiritual journey, there’s probably no single individual who has been more influential. And I discovered him thanks to a Lutheran teacher.

I’ve already talked about my cognitive dissonance at the discovery that Lutherans, whom I believed weren’t Christians, loved Jesus as much as any Baptist I’d known before. Sure, some of their teachings were different–In fact, one day we spent nearly the whole day debating infant baptism with every teacher in every class–but they lived lives that demonstrated the love of God.

But my religion teacher my final year of high school took the cognitive dissonance to a whole new level.

He looked like Jesus. Or, the Western, white version of Jesus that most American Christians picture. He had shoulder-length hair, a beard, and ear piercings. He played the drums during worship time in chapel. He venerated Mother Theresa, Greg Boyd, and, it turns out, Shane Claiborne. He was at once the embodiment of white Jesus and exactly the opposite of what my Baptist upbringing taught me a Christian should be.

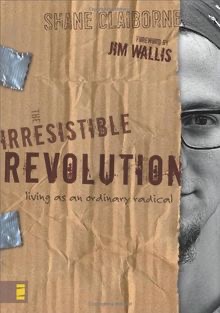

In Dean Dunavan’s class I was quiet. I didn’t engage as much as others in my grade. I’m still this way when it comes to deep conversations. I need to think for a while before I feel prepared to respond, especially when I don’t feel 100% confident in my contribution. But I listened. He assigned us to read the book Irresistible Revolution by Shane Claiborne, a Christian activist and author who was incredibly influential in the lives of many young Christians of my generation.

In his book, Shane Claiborne envisioned a new way of living out the Christian faith. A new way of life that asks questions like, “What if we took seriously the commands of Jesus when he says to love our enemies and to love our neighbors as ourselves?” He was strictly pacifist, and perhaps not communist, but at least communitarian in his way of thinking and living.

And I had an incredibly strong reaction against it.

I had been raised with answers, with a certain way of thinking about Christianity. Shane Claiborne questioned nearly every belief I held dear. It’s been years since I read the book, and I remember very few of the specific things he discussed in the book. What I do remember is the way he made me feel. It’s the book that planted a seed that has continued to grow throughout my life.

Shane Claiborne envisioned a world where Christians lived together in community, across theological lines, with a focus on changing the world serving our neighbors. He took to task the rich who tried to explain away verses where Jesus instructs the wealthy to give up their wealth. He wondered what the world would be like if we chose to love our enemies instead of going to war against them.

Those are just a few of the things I got out of reading the book. Again, I don’t remember a lot of the specifics, but I do remember how it made me feel. At first I was upset. But over time, as I thought more deeply about it, I came around to his point of view.

But there was a problem.

The problem is that I was still part of a fundamentalist Baptist church, and there was no room for this kind of thinking in those churches. And so, as things continued, I grew further and further from the church I had been brought up in.

And then there were the Lutherans. They were definitely more open than the Baptists, but they still very much fell into the white, suburban category. It didn’t help that it was a private Lutheran school, so the kids tended to come from upper middle class families.

And so I felt alone. Sure, there were people who were as engaged with what we were reading as I was. Sure, there were people who developed some revolutionary ideas. I think, however, that most of them lacked the experience of living in a poor family with parents who struggled to pay their bills every day. I still don’t know how my parents managed to enroll me at the school and keep my tuition paid. The thing is, when you’ve seen firsthand the cracks in the systems that are meant to support the lower systems of society, it has a way of radicalizing you. This is especially true of people who are exposed to ideas that present a dream of how things could be better.

I caught this dream. I caught it fervently. That same year I read The Jungle by Upton Sinclair, a radical socialist author, for one of my English classes. This story about working class families who were under the thumb of the Chicago meatpacking elite really spoke to me. I went on to read many of his other works.

But I never lost my fundamentalist faith. Part of it was definitely the fear of going to hell that was instilled in me from a young age. But I think it went deeper than that. Reading Shane Claiborne and other authors like him showed a whole other side to the gospel. It was a gospel that didn’t only seek to save us from hell, but also to change our whole society into a place where no one would have to go without.

And I wanted to hold onto both of these sides of my faith. I still believed strongly in the gospel of faith and salvation, but I wanted to go deeper into seeking a more just society. I wanted to seek justice within the confines of the church in which I had been raised. And it made me feel isolated.

I felt like I was the only one. The only one who wanted to hold onto both sides of the gospel. The only one who was unwilling to compromise my beliefs in search of justice for all. When I looked into the world, I saw only churches who chose one or the other: Either they would hold onto the gospel of salvation in Jesus Christ and ignore the biblical call to seek justice for the poor and oppressed, or they would hold onto the gospel of social justice and ignore the biblical call to share the good news of Jesus.

But I wanted both.

Searching for a community that both clung to the deep personal spirituality with which I was brought up and the social gospel which I had discovered led me on a long path. It turns out I wasn’t alone in my beliefs. But it took years for me to figure that out.

Life was so much easier before, when things were black or white, when evil and good were obvious, when I didn’t have to figure out the right and the wrong because my leaders would tell me what they were. But now, I began to see everything in shades of gray. The hard and fast barrier between black and white began to break down as soon as I discovered that Lutherans were just as much real Christians as the Baptists I had grown up with. And it continued to fall as I discovered a theology that was open and welcoming to everyone, fighting for justice in a world filled with injustice. Right and wrong were a lot less clear when I discovered that the Bible isn’t as clearly interpreted as I had been led to believe. In fact, there were whole messages in the Bible that I’d never even heard before.

And so I continued walking alone, feeling a crisis of faith. It wasn’t really a crisis in the sense that I was losing my faith. It was a crisis in the sense that there was a lot more to having faith than I had previously believed. And I had to discover for myself what that meant for me.

This journey, which began with the challenging ideas of Shane Claiborne, continues to shape my life today. Now, at 35, I find myself in France, working among refugees, embodying the very principles of love and justice that Claiborne inspired in me. This journey of faith and justice is ongoing, and I anticipate it will continue to evolve, shaping my life and work for years to come.

The problem with writing these narrative posts is that I never know where to stop or how much to include. I could go on. And on. And on. But I’ll stop for now. The influences of Shane Claiborne, my religion teacher, and Upton Sinclair kicked off a process that has deeply and profoundly changed me. In fact, I still believe I’m changing. I’ll never be the same person who was so sure of my faith and my beliefs that I was as a young person. Life was easier then, but I don’t ever want to go back.

In fact, I’m just getting started.